Notable Winners of the Controversial Turner Prize in Its Early YearsI was excited when the shortlist for the 2018 Turner Prize was publicised in April 2018, and the countdown to the announcement of the winner in September started. With this hype, contemporary arts enthusiasts all over the world were once again reminded of some of the controversial art greats who have won the prestigious prize. Here some of the most memorable winners from the early years. 1984, Gilbert & George – Coming Calmly filthy, ego-driven and aggressive, the psychedelic photo-montage by Gilbert & George took the prize in 1984, even though the artists were not keen to accept it. They said, “We don’t like prizes…” 1993, House, Rachel Whiteread Known as the first woman to win the Turner Prize, Rachel Whiteread had to get her hands full of cement for this achievement. She created a ‘house fossil’ by stripping the exterior of a house in London after filling it with concrete. 1995, Mother and Child – Damien Hirst Indisputably one of the most famous pieces of art ever created, and likely some of the most famous dead animals, Damien Hirst’s winning piece features a cow and her calf cut in half and suspended in glass tanks. 1997, 60 Minutes of Silence – Gillian Wearing

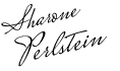

Gillian Wearing directed a film of actors dressed as policemen standing still for an hour. The piece is particularly memorable because Wearing stormed out of a live discussion of the piece on Channel 4 News. 1998, No Woman No Cry – Chris Ofili Known for using the interesting medium of elephant dung coated with polyester resin, Chris Ofili created the winning piece in 1998 which depicted a black woman heartbreakingly weeping over the death of Stephen Lawrence, a teenager who was murdered in South East London in 1993.

0 Comments

Frieze Fair Is Focusing on Women Artists in Its Upcoming Exhibition – ‘Social Work’In 2017, Frieze London presented Sex Work:

Radical Art & Feminist Politics, a show that presented the work of radical feminist artists from the 1960’s and 70’s who had been censured during their career. This year the Frieze Fair will be tackling another controversial feminist theme with Social Work, which will focus on the extraordinary contribution of female artists during the 1980’s. More than making a statement on gender inequality in the arts, the fair will celebrate the work of powerful women artists by giving them the exhibition space they had been denied in the past. For so many years the art world was largely dominated by male artists with contributions made by female artists relegated to the sidelines. Even prominent artists like Jenny Holzer and Cindy Sherman had to find alternative spaces to show their works. The all-female curatorial panel for the upcoming show includes Iwona Blaznick, current director of the Whitechapel Art Gallery, as well as other luminaries of the international art world: Jennifer Higgie (Editorial Director, frieze), Melanie Keen, Polly Staple, Sally Tallant (Director, Liverpool Biennial of Contemporary Art), Fatos Ustek, Zoe Whitley, Lydia Yee, Katrina Brown, Louisa Buck and Amira Gad (Exhibitions Curator, Serpentine Galleries). Breaking Rules in The 1980’sThe 1980’s was a decade that demonstrated a return to painting especially by male artists. The exhibition “A New Spirit in Painting” held in 1981 at the Royal Academy in London was an all-male affair that reflected the fact that female artists of the time were finding it hard to compete for exhibition space. This despite the fact that many female artists were challenging the boundaries of contemporary art, moving into multimedia, performance and video art. While male artists were returning to neo-classicism their female compatriots were exploring the future, challenging the status quo and embracing activism in their art, but still they had no room in the traditional exhibition spaces, and they were unlikely to be able to survive solely as artists. Has Anything Changed? While exhibitions and shows like Social Work and Sex Work do much to celebrate the contributions of female artists often ignored by mainstream media and galleries, there is still a disparity between the numbers of male and female artists being shown today. Marijke Steedman of the Freelands Foundation noted that only 22% of solo shows presented by London galleries were by female artists, which is a dip in numbers of around 8% compared to 2016. There is an even stronger decline in the numbers of women artists represented by top London galleries. In 2017, only around 28% of artists represented by galleries in London were female, another drop since 2016 of a whopping 29%. The Frieze Fair doesn’t seek to redress the issue by replaying the past, but to celebrate and bring to the fore the contributions of female artists, largely forgotten, often ignored by the major galleries during the 1980’s. . Jacob Hashimoto Talks About ‘The Eclipse’ and ‘Never Comes Tomorrow’ New York City artist Jacob Hashimoto is known for his large-scale installation pieces. Born in 1973 in Greeley, Colorado, Hashimoto draws on his Japanese heritage to create complex worlds from components such as paper kites, colorful disks and political stickers. His works are multi-layered and have references to a range of topics including cosmology, political protest, and even video games. Hashimoto’s work is often colorful and amorphous, can be happy or gloomy – and is usually made up of multiple components, expertly layered. It is always intricate and eloquent. A wave of dark and light One of Jacob Hashimoto’s most recent works is ‘The Eclipse’, a wave of black and white disks suspended from a ceiling – it resembles a tornado. Each disk is a hand-crafted paper and wood kite – and there are over 15,000 of them! ‘The Eclipse’ was conceived during the period leading up to the American elections and constructed after Donald Trump took his seat in 2016. The piece was first shown at the 57th Venice Biennale and later in the UAE in Dubai at the Leila Heller Gallery and currently resides in St Cornelius Chapel on Governors Island off the Manhattan coast. A blood-red screen-print of the American flag is printed on the back of the black kites but is only visible in certain light. In an interview, Hashimoto said that this expressed that there is a storm coming to America and that this particular work symbolized the eclipse of three decades of progress in America. Hashimoto believes it is patriotic for citizens to talk about what they feel is happening in their country. History and cosmology merge in an understated political statement Installed near ‘The Eclipse’ on Governors Island, there is yet another one of Hashimoto’s works. The ‘Never Comes Tomorrow’ installation was created with steel, ABS, wood, LED lights and vinyl stickers. It consists of two large steel funnels. One is made up of a mix of colorful and transparent spheres, the other abstract shapes changing to rectangles in shades of green and blue. The funnels resemble vortexes and have hundreds of small wooden cubes emerging from the tails that meet in the center. The cubes house stickers, some made by Hashimoto and others collected at a Women’s Day protest against Trump’s inauguration attended by the artist. Some sport slogans like, ‘Not My President’ and ‘Refugees Are Welcome Here’. ‘Never Comes Tomorrow’ is installed in Liggett Arch, a deep passageway in a former infantry housing space. The design clearly references Hashimoto’s deep interest in both history and cosmology. Hashimoto disclosed that he had some concerns about the political stickers on the piece but the piece was installed at such a height, the stickers are not really visible to the public. The artist considers ‘Never Comes Tomorrow’ to be a self-portrait. He built it while he was working with the Natural History Museum in New York in collaboration with an astrophysicist on a range of paintings of exoplanets. This was part of what influenced Hashimoto in creating the piece. He was also inspired by Tiffany lamps – something that featured in Hashimoto’s opinion on cultural appropriation. Whose culture is it anyway? Pablo Picasso said, ‘Good artists copy, great artists steal’. Cultural appropriation has been a contentious topic for decades, and yet it has featured in art for centuries – ust look at how similar Greek and Egyptian sculptures are. Jacob Hashimoto acknowledges that the history of art is filled with cultural appropriation and admits that he is also guilty of this. He is interested in how Tiffany assimilated an Asian decorative language with classic American art objects. And Tiffany was only one of many examples of cultural appropriation in the arts. Matisse was also a cultural appropriator. He rendered odalisque fantasies as paintings of Middle East harems. So was Claude Monet who painted his wife dressed up in a traditional Japanese kimono. In creating ‘Never Comes Tomorrow’, Hashimoto intentionally stole from Tiffany by building giant black holes that resemble Tiffany lamps. Dark titles for works light as air Jacob Hashimoto’s work is usually approached by art critics as having tranquil qualities. His Japanese heritage is often connected with his art and discussions around the meditative qualities of the pieces occur. According to Hashimoto, leaving the work to speak for itself will encourage this narrative, but believes it’s possible to push people into stepping back and questioning the meaning of the work through a simple technique. This method involves pairing off ethereal and light works of art with deep, heavy and thought-provoking titles. Whether it is psychosexual, long and complex, or simply crazy, the juxtaposition of awarding a light work with a dark title instills curiosity in viewers and forces them to rethink their initial assumptions about the meaning behind the piece. Vibrant and decorative, or dark and gloomy – it’s all goodColor, patterns, or both are richly featured throughout Jacob Hashimoto’s work. Works like ‘The Eclipse’ are not colorful and gives a more somber impression than works like ‘Light, Like Static Vanished into Shadows’ a work which is particularly vibrant and colorful. Crafted with acrylic, Dacron, bamboo, paper and wood, it features explosive color and repeated patterns. The viewer’s eyes are drawn for one line to the next – some are left feeling cheerful, others merely frantic. The question is whether the artist considers how color will affect the overall mood of the work as he is constructing the piece. Color can be therapeutic Hashimoto asserts that he is not a colorist as such, and does not use any procedure to attempt to create a mood. At the start of his journey as an artist he used color as a device to get people to notice his work – he hoped that this would compel them to decipher the language his work speaks. Hashimoto now approaches color intuitively and often attempts to find awkward color situations. He also believes that making colorful and powerful art can create optimism positive energy. This not only results in a powerful end product but is also therapeutic for the artist. In most countries, whenever budget cuts have to be made, the arts are invariably threatened. And yet, the arts make up an industry with the potential to make a massive, positive impact on society. Here, then, are some of the main reasons why the arts should be supported: 1. They strengthen the economy: While also increasing tourism, arts and cultural goods add billions to the economy and support millions of jobs. 2. Arts improve wellbeing: Studies have found that art is uplifting and creates positive experiences. If you partake in the arts, doesn’t it make you feel happier? 3. Communities are unified: The arts can help people to better understand other cultures. They bring communities together, regardless of age, race and gender. 4. Participation in the arts improves academic performance: Students engaged in arts tend to have better academic results as well as lower drop-out rates. We must always remember that the arts are an essential part of a well-rounded education. 5. Arts programmes can help us to provide better healthcare: More and more healthcare providers are implementing arts programs for patients, families and even staff members. The healing benefits of these programs are finally being acknowledged! 6. The arts have a highly beneficial social impact: Researchers have found that a high concentration of the arts in an area is directly linked to improved social cohesion, greater civic engagement and lower poverty rates. 7. The arts allow like-minded, creative individuals to meet and connect: By enabling people to share experiences at art shows, live performances, music or drama clubs and elsewhere, the arts provide not only entertainment but also unique opportunities for positive connection with other arts enthusiasts. 8. Participation in the arts sparks creativity and innovation: Nowadays, business leaders are increasingly looking for creativity as a key attribute in their staff. There is a growing acknowledgment that thinking creatively and outside the box is the very foundation of the kind of innovation that drives business forward. 9. The arts can promote improved mental health: Have you heard of art therapy? Many different kinds of art-related therapy are now available. Among these is drama therapy, which has been found to be effective in treating insomnia, PTSD and other emotional ailments. 10. Let’s end with the most obvious benefit of all. The arts are fun!:

Visit a gallery or a museum, watch a dance show, see a play or read a book. The arts offer endless opportunities for enjoyment, which – needless to say – is important in itself. Governors IslandImagine escaping the hustle and bustle of city life and sailing off to a stunning island that’s also a hive of art activity – in just 10 minutes. Well, I’ve discovered that if you live in New York, you can do just that! Governors Island is a former military base and a national park that has been transformed into a cultural destination. All it takes is a short hop on a ferry to get to this picturesque art and architecture hub where you will find a host of art galleries and coffee shops – always an excellent combination!

Historical Structures Transformed into Contemporary MasterpiecesMy first stop was Nolan Park. Here I happened upon a timeworn stone chapel – Chapel of St. Cornelius the Centurion. Upon closer inspection, the chapel was so much more than met the eye. Inside I was delightfully confronted by a wave of black and white disks suspended from the ceiling. Named ‘The Eclipse’, the installation was designed by Jacob Hashimoto, a New York City artist. I learned that it was an adaptation of an installation that featured in the 57th International Art Exhibition in Venice. I was soon lucky enough to spot another one of Hashimoto’s pieces – this time in Liggett Arch, a former infantry housing space. Entitled ‘Never Comes Tomorrow’, the installation consists of decorated wooden cubes floating above the deep passageway of the arch, introduced by a colourful metal vortex. The Joy of Finding Art in Unexpected Places

I Was Wandering, But I Wasn’t LostAs I continued meandering through the streets of Governors Island, I realized how effective public art hidden in plain sight is. I was inspired to imagine how it can be used to celebrate and encourage creative collaboration between an areas’ historical, geographical and architectural treasures. Can you imagine the urban fabric of every city transformed into a treasure trove of art and culture? I certainly can.

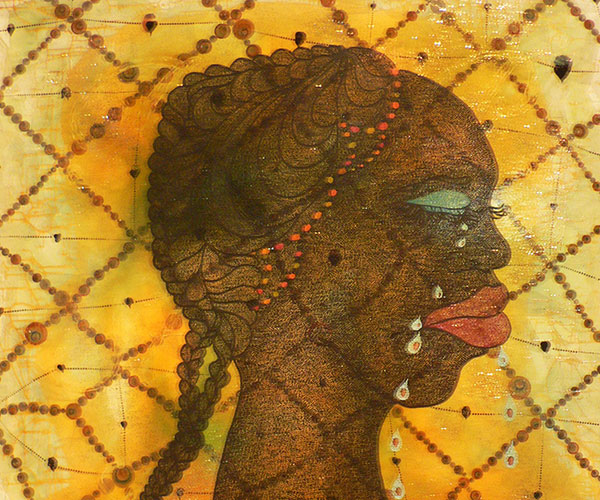

Elusive, Captivating - and Born From RainbowsIt’s hard to pin down how a painting is conjured into existence. It starts with a microscopic dot of inspiration that begins swirling around in the back of the artist’s mind before coming to life in a psychedelic explosion of creativity. Whether the finished art piece is a colorful abstract display or a somber street scene in gray-scale, it has a story to tell. And in each story, a small aspect of the artist is revealed. Each stroke forms part of a complex and enormously personal adventure. Contrast - In Reflection of Organized Chaos

Just Like The Inception of LifeWhen we are born, everything is bright, new and colorful. Then – even though layers of life change the picture of our existence, the original (and true?) colors still find their way to the surface. Like life, art is dependent on love and sincerity – it is not only about hard work and time. What makes a work of art truly exceptional simply cannot be decided by the obvious, it is not how many hours were spent on creating the work. No matter how many strokes you lay down on that canvas, if they are not done with heart (love), and if they are not honest, the piece will ultimately fall flat. Think of Pablo Picasso who said, ‘It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child’. Painting with love and sincerity is painting like a child… freely, with abandon, and with joy. After all, art comes from one place – the heart.

Beyond the Aesthetic of Minimalism Post-Minimalism can be a hard concept to pin down. That’s largely because the term refers not so much to a single, unified aesthetic as to a range of interrelated styles that arose during the late 1960s in the aftermath of Minimalism. Although the different strands of Post-Minimalism overlap with each other, they frequently have diverging, even contrary, approaches and perspectives. Within this broad church, for example, we find not only conceptual painting, sculpting, and photography but also performance art, process art, body art, and site-specific art.

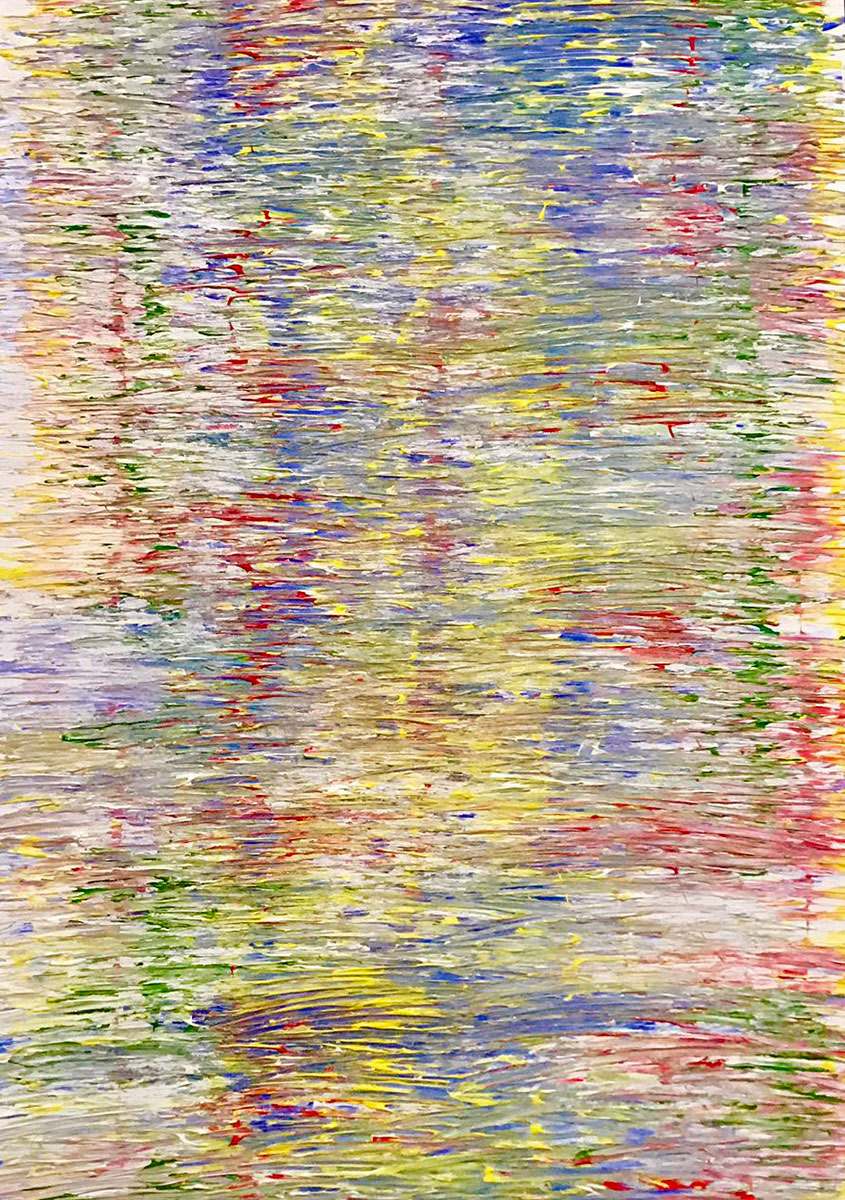

What is the “Post” in Post-Minimalism? When we try to sum up the elusive essence of Post-Minimalism, we also need to remember that the artists grouped under this term have different attitudes and responses to Minimalism itself. For some, the “Post” in “Post-Minimalism” perpetuates and develops the Minimalists’ desire to create works that are abstract, impersonal and have a striking material presence. For other Post-Minimalists, though, the point is to reject the earlier movement’s formality and impersonal qualities. Some Post-Minimalists have, like the Minimalists before them, played down the intentions of the artists and instead highlighted the sheer materiality of their work. Unlike the Minimalists, though, they have de-emphasized form and composition, opting instead for approaches that allow the material to shape itself by sagging or drooping, for example. This part of the Post-Minimalist aesthetic is called “anti-form”. Post-Minimalism has also changed things by moving away from the gallery and out into natural or less formal environments. Unity in Diversity When we think of some key Post-Minimalist artists and works, the movement’s quality of unity in diversity becomes even more evident. The rubric of Post-Minimalism is elastic enough, for instance, to encompass such different phenomena as Robert Morris’s process art, which prioritizes the act of creation itself over its final product; Vito Acconci’s photographic body art; and Richard Long’s walking-based process art, which leaves trails on the ground. Like Long’s art, Post-Minimalism as a whole leaves fascinating trails as it shapes our environment. Loneliness and AlienationBorn in Dublin on 28 October 1909, Francis Bacon had no one location he could truly call home when he was growing up. His father planned on breeding horses in Ireland, but came to London to join the War Office in 1914. After the war, the family moved around several locations in Ireland in constant fear of being targeted by the Irish independence movement. The asthma that Bacon suffered from made him unable to hunt and engage in the kinds of physical pursuits his father admired. Worse still, in his father’s eyes, was the fact that he was gay, a reality that Bacon discovered and disclosed in his youth. All in all, Francis Bacon experienced a lonely childhood and the sense of social alienation never left him. The loneliness may have been intolerable if it weren’t for his maternal grandmother, who lived in Abbeyleix, Ireland, and provided the young man with some parental warmth and acceptance. Detachment and DestructionAfter spending two months in Berlin in 1927, 18-year-old Francis Bacon traveled to Paris where he was profoundly moved by a Picasso exhibition. From this point on, he was resolved to become an artist, but as a reflection of the general state of his social class – the disposed Anglo-Irish gentry – Bacon found himself drifting and rootless. Some initial success finding patrons and critical acclaim for his 1933 painting, Crucifixion was soon dissipated, and very little of the art he created between 1937 and 1943 survived, as he destroyed most of his work at the time. Yet, while the products of his work were lost, his technique, unique take on the human body, and artistic agenda were developing. His life and art were not a sterile void after all Agony and ToleranceFrancis Bacon made a breakthrough as an artist with his 1944 painting, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. Here, the major themes that made the rest of his career a success are present. The figures, vaguely human, seem agonized and violent. Francis Bacon often quoted Aeschylus’s phrase, “the reek of human blood smiles out at me”, in relation to this work, and the ambiguity here served him well. Was he exploring taboos of blood, saliva, flesh and bone in order to revel in them as someone with no moral care for the human species, a kind of visual psychopathy? If it was as simple as that these paintings would not be as disturbing and haunting as they are. They work because Francis Bacon embraced all that is human, including our taboos, and he did so unflinchingly. Embracing AngerIn 1953, Bacon found a means of making his own pain universal. He painted his ‘Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X’. This was a subject to which he returned time and again, at least forty-five of his paintings addressed the same image, that of Innocent X in his pontifical chair. Francis Bacon himself playfully explained this fixation by saying that no other subject allowed him to paint such purple colors as did the pope’s clothes. But the viewer is inevitably struck by the crucial distortion that Bacon brings to the 1650 original.

Bacon’s pope, whose face is often skeletal, is screaming in anguish, confined to his chair. This evokes a feeling far more profound than a critique of church authority. It causes the viewers to see themselves as mortal, constrained and howling in grief. It reveals the pain that lies under the surface of existence. We may relish our place in the world, but the furies are never far away. By daring to embrace the aspects of humanity that we normally shy away from Francis Bacon translated his own distress into the universal language of pain. His works can shock, even now, let alone in the context of mid-twentieth century art DedicationAndy Warhol was so dedicated to being an artist that he overcame major physical and emotional challenges. Warhol was born in 1929 to poor parents who had emigrated to America from modern day Slovakia. He grew up in Pittsburgh, where he had a difficult childhood, due to his suffering from a medical disorder called Sydenham’s chorea. This serious condition, which causes loss of motor control over limbs and involuntary facial twitches, was a terrible blow to young Warhol’s ambitions. Not only were there physical challenges he had to face, but having to spend weeks at a time in bed, he was also socially cut off from his peers. Nonetheless, he overcame the disease if not the sense of isolation, to study commercial art at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, graduating with a BA in Fine Art in 1949. Being at the Right Place at the Right TimeAndy Warhol had a profound grasp of the revolution of the 1960s. Having moved to New York to work in advertising and illustration for magazines, Warhol was perfectly placed to witness both the explosion of mass production and marketing and the rise of a counter-culture that apposed the crassness of modern advertising. Warhol’s art embraced both developments. His work began to be displayed in galleries in the late 1950s and early 1960s. From this ‘Pop Art’ period comes his famous, repeated images of quintessential American people and objects: Marilyn Monroe, Mohamed Ali, Elvis Presley, Campbell’s Soup Cans, electric chairs, dollar bills, Coca-Cola bottles, etc. Profound HumorSatire and subversion can have a powerful impact. Some early critics misunderstood Warhol and thought that he was embracing US capitalism, that his paintings were merely ads. But when you take an advertising idea or image and exaggerate it, draw attention to it, repeat it and place it in a gallery it changes its meaning. The artwork becomes both a mirror on the world and an iconic artifact in its own right. The mockery in Andy Warhol’s approach to art often makes the impact of his prints and paintings deeply subversive. At times, his work even evokes anger at the distasteful use of matters like the death chair or fatal car accidents as commercial promotion tools and topics. PRAndy Warhol made himself a celebrity as well as an artist. He is the one who said we each have our ‘fifteen minutes of fame’. He had a knack for advertising, he knew how to be accurately provocative and get the right kind of attention. Warhol founded ‘the Factory’, his New York studio, where he surrounded himself with ‘art-workers’ who helped him produce silk screens and films in an atmosphere of permissiveness, parties and amphetamines. The fact that he was at the center of a larger network of artists meant that even when the momentum behind the appeal of his own works faltered, interest in him would be revived by the success of someone he had mentored.

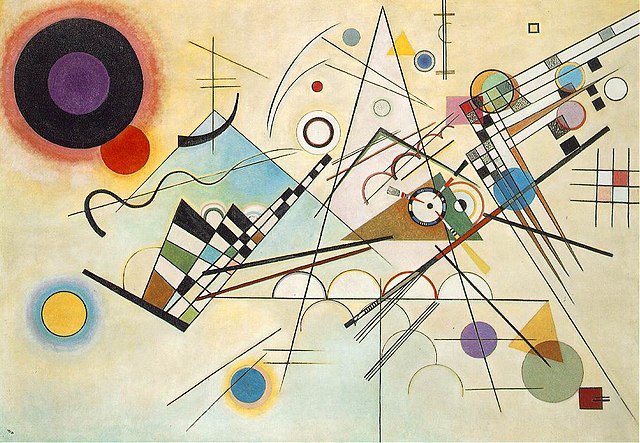

Andy Warhol died in 1987 and his works have gone on to be extraordinarily collectible. In 2013, ‘Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster)’ sold at auction for $105.4m.  Even before the profound rupture of the Great War and the political revolutions that followed, a revolution in culture had taken in the first decade of the twentieth century. And in the visual arts, almost no one was so transformed by that revolution as Wassily Kandinsky. He was born in Moscow in 1866 and studied art in Odessa at the Grekov Art School. He then moved on to study law and economics and only returned to art in his 30s. Kandinsky’s early works are beautiful in the warmth of their colors, but conventional. As he began to think about the challenges of modernism in music as well as art, Wassily Kandinsky gradually became even more daring. The outlines of structures in his paintings began to melt. From 1911 onward, he filled entire canvasses with colored abstractions, and was among the first to produce purely abstract art. From the Concrete to the ConceptualThe challenge faced by all artists in an era where a camera could reproduce scenes more accurately than a painting was to think again about the purpose of their art. For Kandinsky, the solution to the crisis of traditional art was to understand that art functions on two levels simultaneously, it influences both the senses and the mind. Once he had decided to investigate the effects of abstract painting on the mind, he opened the door to a revolution. Spending hours and hours experimenting with the impact of shape on color on his inner being, Wassily Kandinsky came to realize that even apparently simple geometric shapes could carry a powerful aesthetic impact to the viewer. Wassily Kandinsky and the BauhausThe Bauhaus was an avant-garde art school that strove to unite arts, crafts and architecture in a revolutionary and modern fashion. Kandinsky was invited to join the school and there (1922 – 1933) he perfected his technique. His paintings from this period are stunning, in that they use carefully chosen blocks of color to evoke an emotional response in the viewer and selected shapes to challenge the human desire to make sense of patterns. Wassily Kandinsky was among the practitioners persecuted by the Nazis, who included his work in the list of ‘degenerate art’. He was forced to flee and moved to France, where he lived and worked until 1944. “My Six-Year-Old Can Paint Like That…”The case against Wassily Kandinsky, as against many other modern artists, is that anyone can paint in his style, even children. Yet contemplation of Kandinsky’s works evokes such strong responses that there must be more to them than the superficially playful interaction of color and shape. And there is. Wassily Kandinsky himself explained the issue in his 1926 book, Point and Line to Plane. The subjective effect upon the inner mind of the viewer even of points and lines can be profound. The manner in which a line is placed, the angle it makes, is enough to create meaning. A horizontal line evokes the ground on which a person moves, while a curved line suggests powerful forces are at work. Only someone who spends decades mastering color and contemplating on the spiritual and unconscious associations of geometric shapes can produce such masterful paintings as those of Wassily Kandinsky. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed