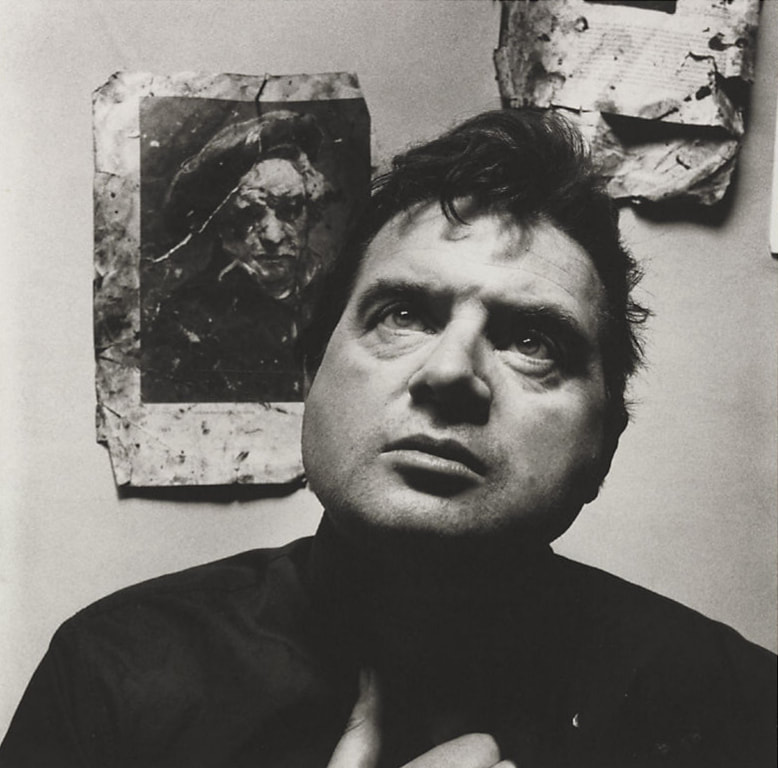

Loneliness and AlienationBorn in Dublin on 28 October 1909, Francis Bacon had no one location he could truly call home when he was growing up. His father planned on breeding horses in Ireland, but came to London to join the War Office in 1914. After the war, the family moved around several locations in Ireland in constant fear of being targeted by the Irish independence movement. The asthma that Bacon suffered from made him unable to hunt and engage in the kinds of physical pursuits his father admired. Worse still, in his father’s eyes, was the fact that he was gay, a reality that Bacon discovered and disclosed in his youth. All in all, Francis Bacon experienced a lonely childhood and the sense of social alienation never left him. The loneliness may have been intolerable if it weren’t for his maternal grandmother, who lived in Abbeyleix, Ireland, and provided the young man with some parental warmth and acceptance. Detachment and DestructionAfter spending two months in Berlin in 1927, 18-year-old Francis Bacon traveled to Paris where he was profoundly moved by a Picasso exhibition. From this point on, he was resolved to become an artist, but as a reflection of the general state of his social class – the disposed Anglo-Irish gentry – Bacon found himself drifting and rootless. Some initial success finding patrons and critical acclaim for his 1933 painting, Crucifixion was soon dissipated, and very little of the art he created between 1937 and 1943 survived, as he destroyed most of his work at the time. Yet, while the products of his work were lost, his technique, unique take on the human body, and artistic agenda were developing. His life and art were not a sterile void after all Agony and ToleranceFrancis Bacon made a breakthrough as an artist with his 1944 painting, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. Here, the major themes that made the rest of his career a success are present. The figures, vaguely human, seem agonized and violent. Francis Bacon often quoted Aeschylus’s phrase, “the reek of human blood smiles out at me”, in relation to this work, and the ambiguity here served him well. Was he exploring taboos of blood, saliva, flesh and bone in order to revel in them as someone with no moral care for the human species, a kind of visual psychopathy? If it was as simple as that these paintings would not be as disturbing and haunting as they are. They work because Francis Bacon embraced all that is human, including our taboos, and he did so unflinchingly. Embracing AngerIn 1953, Bacon found a means of making his own pain universal. He painted his ‘Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X’. This was a subject to which he returned time and again, at least forty-five of his paintings addressed the same image, that of Innocent X in his pontifical chair. Francis Bacon himself playfully explained this fixation by saying that no other subject allowed him to paint such purple colors as did the pope’s clothes. But the viewer is inevitably struck by the crucial distortion that Bacon brings to the 1650 original.

Bacon’s pope, whose face is often skeletal, is screaming in anguish, confined to his chair. This evokes a feeling far more profound than a critique of church authority. It causes the viewers to see themselves as mortal, constrained and howling in grief. It reveals the pain that lies under the surface of existence. We may relish our place in the world, but the furies are never far away. By daring to embrace the aspects of humanity that we normally shy away from Francis Bacon translated his own distress into the universal language of pain. His works can shock, even now, let alone in the context of mid-twentieth century art

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed